The Coach’s Ultimate Guide to Recognizing and Overcoming Cognitive Biases in Baseball and Softball

Whenever we interact with others, we’re bound to have and exhibit cognitive biases.

This proneness to bias touches coaches, athletes, parents, teachers, and students – it really doesn’t matter who you are or what role you fill.

But if you’re an instructor or leader (coaches are both) then acknowledging and overcoming biases is crucial to success.

In this SeamsUp guide, you’ll learn everything coaches need to know about cognitive bias in baseball and softball, as well as how to identify them in your athletes.

We’ll cover the following:

What is cognitive bias?

Examples of cognitive bias

- Status Quo

- Confirmation Bias

- Macabre Constant

- Cognitive Bias

- Observer Bias

- Attribution Bias

- Blind Spot Bias

- The Halo Effect

- Self-Serving Bias

- Catastrophizing

Strategies for overcoming bias

- Context Effect

- Self-Serving Bias

- Picture Superiority Effect

- Hawthorne Effect

- The Ikea Effect

- The Bandwagon Effect

- The Dunning Kruger Effect

Let’s dive right in.

What is Cognitive Bias and How Does It Affect Baseball and Softball Coaches and Athletes?

Cognitive biases are unconscious and often recurring errors in thinking that come about from issues related to one’s memory, attention, and other mental mistakes.

Ultimately, such biases result from our brain’s efforts to simplify the immensely complex world in which we find ourselves in.

As a result, cognitive biases lead to us being irrational in the way we seek, evaluate, interpret, judge, use, and recall information – not to mention in the way we execute decisions.

But to really understand cognitive bias, you should first understand heuristics.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts our brains create to help us make quick decisions and carry out daily tasks without wasting cognitive energy or getting overwhelmed.

On a typical day, our senses are overloaded with incoming information – about 34 gigabytes to put it in digital terms.

That’s a lot of sensory input.

To keep from getting saturated, our brains developed these subconscious coping mechanisms – heuristics.

Heuristics are like automations. When you automate any process, it runs without you having to intervene.

Sometimes, though, an exception case gets fed into the automated process and it produces the wrong result.

Cognitive bias occurs when something happens that doesn’t fit in with our established worldview, and we try erroneously to make sense of it.

These biases are important for baseball or softball coaches because they can either help or hinder player development. Biases can affect aspects of your coaching style or how you instruct your athletes.

Additionally, your athletes’ own biases impact their ability to grow in the sport.

Learning to recognize and deal with cognitive bias is also essential to baseball and softball players’ overall success.

Examples of Cognitive Biases in Baseball and Softball

You may not be able to name a specific bias off the top of your head, but once you read the explanations below, you might recognize them in your own or your athletes’ behavior.

Here are 10 common examples of biases that could affect your coaching:

1) Status Quo Bias

Any time you say or hear the phrase, “but we’ve always done it this way,” status quo bias is at work.

Maintaining the status quo is keeping things as they are or have always been. Resisting change because of the status quo is a common form of bias.

When you are enmeshed in this bias, any change to the current situation or system is seen as a loss, as negative rather than positive.

Status quo bias often gets in the way of meaningful progress or improvement.

Sticking to the same drill or training routine for no other reason than it’s what you’ve always done hinders your athletes’ development.

Good coaches are willing and open to accept new perspectives and incorporate changing insights on things like mechanics or approach.

2) Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is understanding or interpreting information in a way that confirms your own beliefs.

Even when presented with objective facts, you can view them in a way that aligns with what you already believe. Confirmation bias is especially strong if you’re defending your own opinion.

You are more likely to dig in your heels as a default reaction when your beliefs are challenged instead of adapting to and incorporating newly presented information and insights.

For example, you might have an unfavorable opinion about another coach.

When you play that coach’s team and notice he or she shows up late, you confirm and reinforce your negative opinion of him or her. You don’t stop to consider external factors that may have influenced this tardy behavior.

Unfortunately, this same bias can affect how a coach or scout views certain players.

Some bad word of mouth or one negative moment has the ability to color all of your future perceptions of given athletes towards positivity or negativity.

This bias is so prevalent in us all that part of your coaching or scouting methodology should acknowledge and seek to actively counteract this tendency.

Confirmation bias also rears its ugly head when you seek out information to confirm a hypothesis. Rather than obtaining objective facts to test whether you’re right or wrong, you only search for and collect evidence that supports your position.

This can be seen in private lesson coaches who formulate what worked for them in their playing days or with one standout student they’ve had as a full-proof theory for a hitting/pitching/training style or technique that should be applied universally.

Such coaches will search for and hold up clips of elite players that support only their initial hypotheses without being open to debate and examples that refute or even just complicate their argument with nuance.

Coaches and their athletes can both fall victim to the alluring power of confirmation bias.

The best way to avoid it is to stay intentional about open-mindedness and systematically gather facts before passing judgment.

3) Macabre Constant

The Macabre Constant is a theorized bias in educational or skill assessment, which says that coaches tend to unconsciously group athletes into three groups based on ability.

You clump all the high-skilled, medium-skilled, and low-skilled players on your team (or within your client pool) into their respective categories sometimes without even knowing it.

And it’s common to do this in a way that misses or disregards the actual objective ability of certain players.

I’m not necessarily talking about ballplayer skill groupings based on the following process:

You rigorously collected meaningful metrics from various analysis technologies and coupled these insights with enough in-game statistical results to be relevant before using your expertise to parse and distill all of this data into an informed categorization of each player you work with.

Employing the above process will help you be as objective as possible.

But anyone who has been around our games for a while knows that even if player evaluations do actually happen this way, concrete metrics and stats are almost never the only things considered.

The so-called “eye test” or assessing a ballplayer’s confidence and competence levels as some undefined function of perceived “swag” are two common ways that baseball and softball coaches introduce mostly unhelpful noise into the process of player categorization.

Collecting subjective impressions and “intangibles” like these are gateways to the macabre constant bias.

Blunt categorizing and pattern recognition were incredible mental shortcuts that our most-ancient ancestors developed to identify things like predator/prey, tribe/outsider, or edible/poison.

But once societal interactions grew in complexity – and the realities, motivations, and pressures of sports teams or private instruction are rather complex – these shortcuts begin hindering human progress.

This kind of bias sets your athletes up for failure, as you often try to cater or segment aspects of practices and entire lesson sessions to each group.

Subconscious categorizing also leads you to make decisions based on your perceived groupings rather than on players’ real talent – or even on perceiving their still developing or completely stagnant skill level.

Once a player is situated firmly in your mental box – whether the box is marked high, medium, or low – it’s easy to miss or ignore either their continued progress or lack thereof. Some players’ development plateaus, while others keep climbing to the point that you barely recognize them between seasons.

Therefore, the scientific method coupled with radical honesty is the way to go when evaluating your players.

Look at each athlete individually, including their strengths and weaknesses. And do this open-minded looking regularly.

Player assessment is definitely not “set it and forget it.”

4) Cognitive Bias

I include cognitive bias on the list of biases in order to explain the concept in further detail.

General cognitive bias is one of the most common types of human bias because it’s a general term for irrationality.

When your brain receives information that is at odds with what you previously believed, it causes discomfort. One example of cognitive bias affecting your decision-making is choosing a workout program for your team based on your personal experiences rather than the latest research on athletic training.

Or maybe one of your assistant coaches wants to try a new drill that seems to go against what you’ve learned or believed relevant before.

If you prevent your team from trying a new workout or running a new drill despite proof that they work, you’re unable to reconcile the bias in your mind.

Unfortunately, a general cognitive bias is one of the hardest biases to correct.

Often, you may not even realize the extent of bias in your decisions.

The best approach is to hold yourself accountable for your actions and always be willing to listen to advice – whether it comes from players, parents, or other coaches.

5) Observer Bias

Observer bias is an interesting concept that applies aptly to sports coaching.

Observer bias occurs when you influence the behavior of someone you’re watching – simply because you’re observing.

To put it more simply, your athletes behave differently when they know you’re watching them. If they’re aware you’re paying attention, they might sprint harder and dive for that fly ball.

Obviously, you want your players to try their hardest at all times, even when you’re not watching them, because you will not be there all the time.

As a coach, especially at the lower youth levels, you might be subject to observer bias too.

Do you behave a bit differently at games than at practices, because you know parents can observe you at games?

Observer bias can be used for good – if watching someone improves their performance than so be it – at least they’re performing better.

Ideally, however, both you and your players will present the best versions of yourselves no matter who’s paying attention.

Strive to be the best coach you can all the time, and encourage the same behavior in your athletes.

6) Attribution Bias

Attribution bias occurs when you make a judgment about someone else based on your own beliefs or assumptions.

When you jump to conclusions or blame others for things that have nothing to do with them, you exhibit attribution bias.

Attribution means determining the cause of something.

You might attribute behavior (yours or someone else’s) to internal or external factors.

Internal factors are based on a person’s characteristics, and external factors are based on the situation or circumstance.

A very generic but common example of attribution bias is attributing your behavior to external factors and others’ behavior to internal factors.

You assume someone has done something wrong based on a fault of their own, something intrinsic to their character, without considering the external circumstances that might have led to the behavior.

Coaches tend to use attribution bias when they place too much value on their athletes’ abilities and not enough on their environment.

Sometimes, it’s reasonable to factor the weather, the crowd, the playing field’s conditions, or what’s happening in a given player’s personal life into an athlete’s performance during a game.

You would counter (and I would agree wholeheartedly) that truly great ballplayers transcend environmental circumstances.

But the truth is, not all ballplayers you teach privately or coach on a team will be great, and it’s still good to be able to parse the difference between a worthless excuse and a valid factor worth calculating before finalizing your lineup card or asking a private client’s parent to consider working with a different instructor.

Wanna grow your baseball or softball coaching brand?

Get connected to new local and online lesson clients—along with all the tools you need to scale.

Download the free app

That said, here’s a much more palatable example to most coaches’ ears.

Say you give private hitting lessons, and one of your clients seems distracted, less than eager to learn, and like they aren’t giving each rep their all.

If you were to fall into attribution bias, you might think to yourself that the client is lazy, unmotivated, and doesn’t really care about progressing in the game.

Of course, this diagnosis might be true.

But the client’s lackadaisical performance may just as likely have nothing to do with such internal factors.

Instead, the client may be experiencing problems at home or at school; they may be consistently sleep deprived due to various circumstances, like a parent’s early work schedule coupled with regular barrages of late-night homework; or they may have very poor nutritional habits and be under-fueled by the time of your afternoon lesson.

It could also be a combination of such external factors or even some combination of internal and external considerations.

The sheer complexity of the above example highlights that striking a balance between recognizing and responding to internal and external factors in your athletes can be challenging.

The best thing you can do is listen to your players and encourage them to reflect on their own progress.

Just realizing the complexity behind many of the behaviors you observe in your athletes is half the battle to being a better coach.

7) Blind Spot Bias

The blind spot bias is being ignorant of possessing any bias.

You see yourself as rational and hold on to your beliefs even when there’s evidence to the contrary.

Blind spot bias might be one of the most dangerous biases on this list since it makes you believe you have no biases. If you consider yourself rational and are simultaneously unable to be swayed from your positions, it can be hard for others to convince you otherwise.

So how do you deal with blind spot bias as a coach?

Ask your players and other coaches for their opinions. Tell the people around you that it’s okay, even welcomed, to ask questions and seek out the reasons behind what you teach.

The more you have your judgment challenged by others, the more likely you’ll be to recognize your biases.

8) The Halo Effect

The halo effect is the tendency to make a decision about someone based on your overall impression of them.

Phrases like, “I can tell within the first few minutes if this athlete’s any good or not” demonstrate the halo effect.

You let one impression influence how you feel about someone’s entire character or performance as an athlete.

You might remember that we’ve touched something similar above when talking about the macabre constant. These two biases can often go hand in hand.

To be a good, fair coach, however, you should learn to assess someone’s skills based on evidence – and the more evidence the better – not on how you feel about them.

9) Self-Serving Bias

The self-serving bias is related to attribution bias. As you’ll start to see, many biases tend to feed off of each other or otherwise cluster together.

Instead of attribution toward others, though, self-serving bias is about how you view yourself.

With this bias, you tend to attribute positive events to your character, skills, and abilities while attributing negative events and outcomes to external factors.

Self-serving bias can lead coaches and athletes to overestimate their abilities and miss opportunities for meaningful growth.

On the other hand, self-serving bias can also demonstrate low self-confidence.

Some people might display this bias in its exact opposite form, attributing your success to external factors and failures to your own innate character. This form of bias will be more common with young ballplayers, especially given the team nature of our sports.

There’s a tendency to blame the team’s poor performance on yourself, and it's great moments on the contributions of others. Your athletes might do this frequently – pitchers could blame themselves for a loss but downplay their part in achieving a win, for instance.

In either form, self-serving bias can hinder development.

You or your athletes might see no reason to try to improve if environmental factors are always to blame or vice versa.

As a coach, you can combat self-serving bias in yourself by taking responsibility for your actions and reflecting as objectively as possible on your performance.

You can also remind your players that it takes the individual skills of each person on the team to win a game, and that players should be confident in themselves and their agency.

10) Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing is the tendency to think of everything as a disaster.

It can be the result of stress or anxiety when you feel like you’re losing control of something.

When one small thing goes wrong, you might blow it out of proportion, letting it snowball until you’re thinking that everything will go wrong.

You may not experience this much as a coach, especially since your players will look to you to keep the team on track. But you certainly might see catastrophizing in your athletes.

Players going through a slump can be particularly vulnerable to catastrophizing.

They might think it’s the end of their softball or baseball career just because they’re having a few bad weeks. Going through a slump or making mistakes can leave players low on self-confidence and motivation.

As a coach, you should encourage and support your athletes by letting them know that slumps happen and they shouldn’t let their mistakes define them, before working together to formulate a game plan that’ll break this slump apart.

How to Overcome Cognitive Bias as a Baseball or Softball Coach

The first step in overcoming bias – as either a coach or an athlete – is accepting that you have them.

Every bias in the above list may not apply to you, but it’s likely at least a few of them do.

Having cognitive biases isn’t a fault, everyone has biases to an extent. The fault lies in denying your biases or not trying to overcome them.

Sometimes, the best way to approach biases isn’t by eliminating them but by using them to your advantage. Recognizing and working around cognitive biases gives us a chance to learn and grow.

Below are seven ways you can either work on your biases or use cognitive bias to your advantage.

1) Context Effect

People tend to remember something better and more deeply if they’re placed back into the same context they learned it in.

This is a type of bias called the context effect, and coaches often use it to their advantage.

Why do you think most coaches prefer to run practices on a diamond rather than in a gymnasium?

Or why teams might play better on their home field?

If you practice on your home field, athletes feel more comfortable there, more familiar in that setting. When it’s game time, they’re more relaxed and the executions they ran during practice come more easily.

Although the context effect has been applied more to educators in the classroom, it still has implications for baseball and softball players on the field.

Field coaches and private instructors have long-known how important replicating the pressures of game situations in practice are to in-game success, context effect is part of the reason why.

2) Self-Serving Bias

I mentioned self-serving bias and how to overcome it above, but you can also use it to your advantage.

Self-serving bias makes people believe in their own abilities, which can lead to better performance.

If you emphasize how training and practice can bolster an athlete’s personal achievements, it might motivate them to work harder and become self-fulfilling.

3) Picture Superiority Effect

Picture superiority effect is the idea that learning is retained better with images than with words.

Think about a time you explained a drill or a game situation to your players.

Did it make sense to them when you explained it in words only? Or were they better able to understand and execute the drill or technique when they saw it in action?

The picture superiority effect isn’t typically applied to sports, but the idea that learning by watching – and by doing – is prevalent in our games.

Coaches should keep in mind this natural bias to favor visual stimulation rather than words alone.

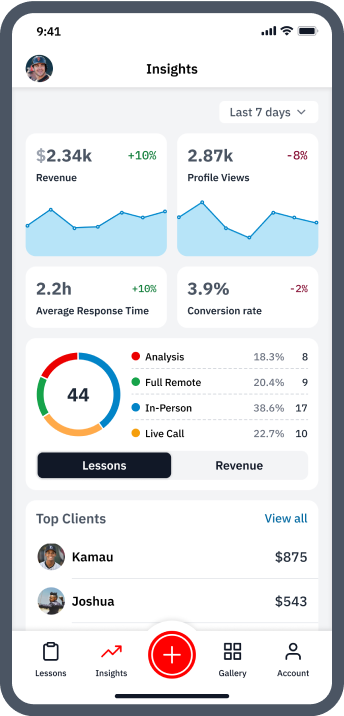

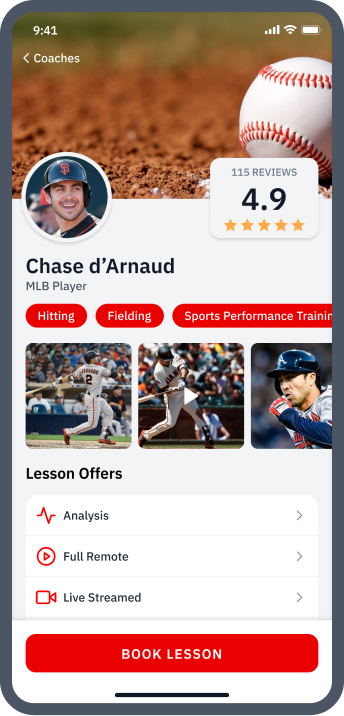

Of course, this effect is baked into nearly everything coaches can offer their players and clients in the SeamsUp app.

4) Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect is related to the observer bias.

It’s named after an experiment done at the Hawthorne Factory in Chicago in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The owners of the factory noticed that their workers’ productivity soared when they were being observed. When the owners stopped observing them, productivity rates returned to normal.

A way coaches can use this effect for a positive outcome is by asking your players to hold each other accountable for their own improvement – this is why team captains are utilized in nearly all sports.

If an athlete’s observer is one of their teammates, they might feel less palpable pressure than they would from their coach, but keep a similar motivation to push themselves.

5) The Ikea Effect

People place an inflated value on things they help create.

They overvalue Ikea furniture, for instance, because they put it together themselves.

You might be more reluctant to let go of an idea if you came up with it and developed it yourself.

The “sunk cost fallacy” is similar, describing how people make future decisions based on the amount of effort they put in previously.

As a coach, you can avoid the biases of the Ikea effect or the sunk cost fallacy by learning when to let go of your projects.

Remember that even though you spent a lot of time on an idea, like a new drill or a fundraiser for your travel team, it may not be the best solution.

Keep assistant coaches or, in case of private instructors, your professional colleagues, around you. And make sure to create a collaborative environment where all opinions matter and are heard, so you always have different perspectives and ideas apart from your own.

A positive use of this effect is found in the powerful coaches’ mantra: “Take ownership of your process.”

When coaches partner with their players to build (or, at least, have a say in) daily practice routines, those players will hold these routines in much higher esteem, which translates into another phrase and concept coaches tend to love: “Buy in.”

Similarly, this Ikea effect can enhance the effectiveness of the physical or mental cues that coaches give to their players or clients.

If the player feels that the cue came about collaboratively and is unique to their voice and personality, they are significantly more likely to internalize the cue and execute it under game pressure.

6) The Bandwagon Effect

The bandwagon effect describes the tendency of people to agree with an idea if they know lots of other people believe it.

Many let other people do the thinking for them, so as to put critical reasoning and individual decision-making aside. All those people can’t be wrong, right?

This psychological concept is one that every sports lover knows all too well.

It’s important to be able to question norms and think for yourself, but as a coach, you can also leverage the bandwagon effect.

Your players might be more motivated to practice on Saturday morning if they know other area teams are doing it too.

Or, if you praise one athlete for hustling during practice, their teammates might follow suit.

With private lessons, you can talk about all the additional training that another client of a similar age is doing between lessons and the amazing results they’ve seen.

In a nutshell, you can use the bandwagon effect to reinforce group norms that you want to see more of from your ballplayers.

7) Dunning Kruger Effect

The Dunning Kruger effect is the tendency for less skilled people to overestimate their abilities on a particular task, while experts doubt themselves.

It’s named after researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger. When studying students, they found that those who scored in the lowest percentile showed the biggest gap between perceived ability and actual test results.

Some athletes might suffer from the same bias. Even if they’re not among the highest-skilled on the team, they might perceive that they are.

This kind of bias can limit athlete motivation – why would they try to work harder if they’re already a top performer?

It can also cause frustration and problems when the athlete’s place in the lineup or recruiting efforts don’t align to their view of themselves.

Although it’s never easy, it’s important to be honest with your players and clients about their current abilities.

Try to set high expectations for them, so that no matter how well they do (or think they do), there’s always another goal to reach. But be realistic to what’s possible, given what you see with this particular player and in light of all of your previous experiences.

The ability to walk this tightrope effectively and consistently is often the difference between elite and amateur coaches.

Final Thoughts

Cognitive biases are unavoidable. You’ll have them as a coach and your athletes will experience them as well.

As long as you learn to recognize your biases and look for ways to overcome them, you can handle cognitive biases in a positive way.

About the Author

Dr. Hannah Whitney, DC

Doctor of Chiropractic at Uptown Whittier Center

Dr. Hannah Whitney is a practitioner at Sunny Hills Chiropractic Center and Uptown Wellness Center. She was also a 4-year college softball player at Alderson Broaddus University.