The History of Pine Tar in Baseball

Pine tar has had a long and interesting history with professional baseball.

Players have been using the brown, sticky substance to get a better grip for decades – and its use has been controversial for a long time.

So why has it been so relevant to the history of baseball?

Let’s take a closer look at what pine tar is, the origins of the MLB’s pine tar rules, and a series of infamous incidents in baseball involving pine tar.

What is Pine Tar and Where Did it Come From?

Pine tar is a sticky substance made from the wood of pine trees that baseball players use on their wood bats for better grip.

The wood is heated and pressurized through dry distillation, producing both charcoal and pine tar.

The stuff was first used as a wood sealant for boats, outdoor furniture, and other items exposed to extreme weather.

Pine tar has its origins in Scandinavia, but it became a major export of the American colonies.

Sailors in New York and Boston once used pine tar extensively to keep their hair in place, prevent the rope from rotting, and protect the ship’s rigging.

Pine tar was also traditionally used as an antiseptic and hoof care treatment for horses.

Eventually, the substance found its way into the hands of ballplayers, who used the tackiness of pine tar to help with getting a grip on a bat or ball.

And if you’re curious whether pine tar makes sense for your young ballplayer to use, don't miss our article on that very topic.

The Origin of the MLB’s Pine Tar Rules

An official ruling on pine tar was added to MLB regulations in 1955.

At that time, the organization was concerned about pine tar discoloring baseballs. But this concern went back much further.

Discolored balls had been considered a hazard ever since the Indians’ Ray Chapman was hit in the head by a discolored ball thrown by Yankees’ Carl Mays and killed in 1920.

The Story of Ray Chapman’s Death

It was the Yankees versus the Indians at the Polo Grounds.

It was a big game since both teams were in the pennant race. And tragedy had found itself a perfect storm of circumstances.

The game had a late afternoon start, so the sky was at the cusp of twilight. And the first stadium light fixtures wouldn’t be erected for another 15 years.

The notoriously mean-spirited head-hunter and knuckle-scraping submariner Carl Mays was tossing for the Yankees.

Ray Chapman, the Indian’s crowd and clubhouse favorite shortstop, was at bat with a 1-1 count – crowding the plate as usual.

In those helmet-less days, ballplayers would simply duck to avoid getting hit in the head.

But the ball was darkened by infield brick dust and pine tar fingerprints, and night was knocking at day’s doorstep – he never saw it coming.

Carl Mays went on to have a 208-126 pitching career in baseball.

Despite this .621 winning percentage nearly identical to Carl Hubbell’s, and a bit better than Bob Feller’s, to this day, there’s never been any movement made for his Hall of Fame induction.

Pine Tar Joins the MLB Rulebook

From 1920 onward, MLB teams were required to provide baseballs with absolutely no discoloration throughout each game.

Baseball clubs were going through a lot of baseballs, having to toss them out every time they were discolored by pine tar during batting practice and live games.

To help prevent teams from losing so many baseballs and wasting money, the Playing Rules Committee added the rule about pine tar in 1955.

So why can batters still use pine tar but not pitchers?

By looking at the official MLB rules on the matter, we can conclude its creators felt that pitchers applying pine tar on their fingers and hands was the main culprit of ball discoloration.

According to this Rule 3.02(c) of the official MLB regulations, players are allowed to cover or treat the bat with “any material or substance to improve the grip” as long as it’s not more than 18 inches. Pine tar is, therefore, legally allowed for hitters.

Relatedly, rule 3.01 prohibits any player from discoloring or damaging the ball “by rubbing it with soil, rosin, paraffin, licorice, sand-paper, emery-paper or other foreign substance.”

And Rule 8.02(b) prohibits the pitcher from attaching any foreign substance to either hand, any finger, or either wrist.

More recently these rules for pitchers have been updated and Major League Baseball began enforcing them like never before.

Rule 6.02(c), is an expansion of Rule 3.01.

It states that a pitcher may not "apply a foreign substance of any kind to the ball;" "deface the ball in any manner;'' throw a shine ball, spit ball, mud ball, or emery ball; "have on his person, or in his possession, any foreign substance;" or "attach anything to his hand, any finger or either wrist (e.g., Band-Aid, tape, Super Glue, bracelet, etc.)."

Modern Major League Baseball officials want to level the playing field in the forever arms race between pitchers and batters.

The Pine Tar Incidents – Yes, There Was More Than One

Most baseball aficionados and some casual fans know about the Pine Tar Game between the New York Yankees and Kansas City Royals on July 24, 1983.

While this is the most famous incident involving pine tar in baseball – because it prompted an official rules revision – it’s not the only one.

There are five more mishaps worth mentioning.

Let’s go over all of them in chronological order.

The Pine Tar Incident, 1975

The 1975 game between the Yankees and the Twins is one of the first MLB incidents involving pine tar to make headlines.

Yankees beloved player Thurman Munson was called out for having more than 18 inches of pine tar on his bat, as pointed out by the Twins’ manager.

The Twins were outraged but didn’t petition the league.

There was still buzz around the pine tar rule later in that season and a general appeal was even brought to the MLB.

But the original 1955 rule would stand as was until the famous 1983 game.

The Pine Tar Game, 1983

The events of the 1983 game between the Yankees and the Royals would force the MLB to put an addendum to the current pine tar ruling in the official regulations.

In a similar situation as the 1975 game, Royals’ batter George Brett was called out for having more than 18 inches of pine tar on his bat – after hitting a game-winning home run.

The Royals protested to the MLB, and this time, the appeal was recognized.

The obscure pine tar rule was revisited, and the MLB added a provision, in the form of a note, on Rule 3.02(c).

It stated that a batter can’t be called out for a pine-tarred bat if the player has already used the bat during that game.

As an aside, it is odd how often the Yankees come up in these pine tar stories.

Brendan Donnelly, 2005

As we all know now, pine tar is legal for batters, but not for pitchers.

Traditionally the rule was largely ignored though, so long as pitchers were relatively discrete about it.

One pitcher who wasn’t tactful enough was Angels’ reliever Brendan Donnelly.

In a 2005 game against the Nationals, Donnelly was caught with pine tar on his glove and suspended for 10 days by the MLB.

Donnelly defended his use of pine tar and even said, in 2012 when our next incident occurred, that he didn’t see what the big deal was.

Joel Peralta, 2012

Tampa Bay Rays’ pitcher Joel Peralta was suspended for eight games when the umpires found pine tar on his glove in the June 19, 2012 game against the Nationals.

The Nationals had a tip from one of Peralta’s old D.C. teammates that he tended to use too much pine tar.

They brought it up to the umpire, who inspected Peralta’s glove and ejected him.

Michael Pineda, 2014

Yankees’ pitcher Michael Pineda was caught with pine tar on his neck in the April 23, 2014 game against the Red Sox.

Pineda apparently wasn’t making attempts to hide it, as umpires could clearly see the brownish stain in his skin.

He was ejected and later suspended for 10 games.

He claimed to be using it to have a better grip on the ball and thus better control during the cold Boston weather, so as not to hit Red Sox batters. His suspension stood anyway.

Los Angeles Angels’ Employee, March 2020

This final pine-tar bust doesn’t feature an MLB player – not even the Yankees.

A 30-year employee for the Angels, Brian “Bubba” Harkins, was fired a few years back for selling a mixture of rosin and pine tar to visiting pitchers.

Harkins’ “Go-Go Juice” was well known throughout the league, earning the long-time Angles employee some extra money.

He was also a well-respected staff member of the Angels organization until this incident.

Final Thoughts on the History of Pine Tar and Baseball

Pine tar has been around baseball for a long time, causing disruptions and disagreements amongst players and fans alike.

Despite MLB’s most recent crackdown, the stuff is still used in the major leagues, and many brands successfully sell pine tar products for use in baseball.

So it doesn’t seem like pine tar is going away any time soon.

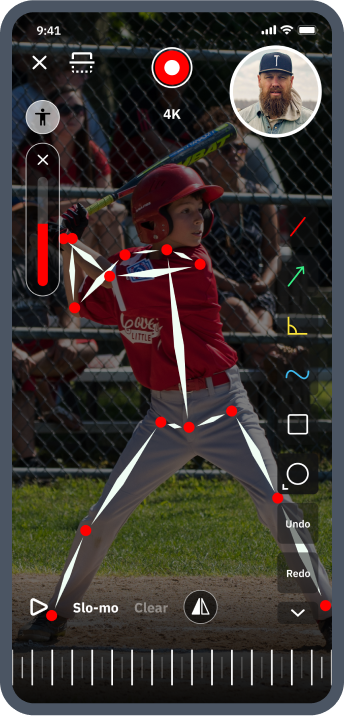

Unlock your ballplayer’s full potential

Find the perfect vetted coach to build a solid foundation or take your player's skills to new heights.

Download the free app

About the Author

Courtney Withrow

Professional Writer

Originally from the U.S., Courtney is a Brussels-based freelance writer with a Master’s degree in International Relations. She grew up playing softball and still loves the game.