“Cue” the Debate: The Ultimate Guide on Internal vs. External Focus Cues for Baseball & Softball Coaches

Across sports, athletic training, and movement science, there’s an ongoing debate about how best to teach.

The goal of this guide is to help you enter this debate fully equipped with all the facts so that you can form your own conclusions as coaches, parents, or ballplayers.

To start, you should know that significant evidence points to the importance of cueing – AKA, how coaches verbally instruct their athletes – in athletic results.

Researchers are specifically interested in the exact role such communication plays in coaching and whether having athletes focus internally or externally makes a difference in learning and performance outcomes.

If you have no idea what we’re talking about yet, don’t worry.

In this ultimate guide, you’ll learn about cueing, the debate between internal and external focus, and how it all applies to baseball and softball coaches.

It’s broken down into seven sections:

- What are baseball and softball coaching cues?

- The importance of communication in motor skills learning

- A brief history of the debate on cueing in sports

- The difference between internal and external focus

- Shifting focus and resulting neurophysiological changes

- How coaching cues affect baseball and softball learning and performance

- Other related debates in motor skills acquisition

What are Coaching Cues in Baseball and Softball?

Cues can refer to what an athlete is thinking about when he or she is trying to perform an action. And these cues enter an athlete’s thinking via verbal instructions that their coaches give during training.

They’re like pointers, describing how an athlete should complete a motion or perform a skill.

It sounds relatively straightforward, but the exact language coaches use to instruct their athletes can impact learning and performance in a big way.

Cues that are too long and complex, for example, are unlikely to teach an athlete what they need to learn and even less likely to be applied in a live game performance.

There are three types of cues – internal, external, and neutral. And we’ll explain what each type entails in just a bit.

And evidence has shown that attentional focus affects performance.

Cueing internal and external focus isn’t just relevant to sports. Physical therapists and other clinicians who work on motor improvement need to use the right cues for their patients as well.

Studying the effects of verbal cues on all kinds of performance and recovery, therefore, has significant implications for how they’re applied in baseball and softball.

Is coaching an art or a science?

Let’s take a quick detour from our guide to all things cueing.

Many coaches will claim that what they do is an art – that it takes practice and development to hone their skills. And it’s a compelling and all but undeniable point.

Indeed, some coaches rely significantly more on their gut and past experiences than on scientific data.

But research studies on coaching try to find a way to better understand it, using measurable evidence to explain how things work.

Much of the research behind coaching cues – and there is a great deal – has been driven by this desire to make sense of the “art of coaching.”

As a coach, where does this leave you?

Do you rely more on your own experiences and those of other coaches, or do you put stock in scientific studies?

Great modern coaches should aim to do both.

Experience is important, but so is progress. Many coaches can benefit from treating their job more like a science than an art form.

Instead of “going with your gut,” especially when talking about the training and preparation that happens before the big game, it’s well worth testing out methods that have been proven effective.

And when you implement new techniques in your coaching, keep track of how well they work and whether you see real improvement with your athletes’ confidence and in-game performances.

The benefit of a scientific approach is measurable, actionable results. What coach wouldn’t want that?

Okay, detour over and we’re back to cues.

A Brief History of the Debate on Cueing

One of the first studies on the effective use of coaching cues was published in 1998.

Scientists Wulf, Höß, and Prinz tested three groups of participants on a ski-simulator.

One group received internal focus instruction, another external, and a third group no focus instructions.

Again, we’ll go into way more depth on what internal and external focus means a bit later, but here's the basics:

And, just in case you’re curious, neutral focus is when the coach attempts to bring an athlete’s attention to non-awareness by not specifying a particular body part nor an environmental feature to focus on. For example, a neutral focus cue could be: “On this pitch, throw with maximum effort.”

The results of this seminal ski-simulator study showed that external-focus instructions enhanced learning of the skiing skill being tested better than internal ones.

After this initial study, many followed. The results were often the same across the numerous sports tested.

Golf swings were improved by focusing learners’ attention externally on the motion of the club rather than the motion of their arms in a 1999 study.

Children learning a soccer throw-in did better when they heard external-focus feedback in another study by Wulf et al. in 2010.

These results led some researchers to wonder if the effects of cueing were different for athletes that don’t manipulate an object, like sprinters or long-jumpers.

But after many more studies, researchers have come to the same conclusion no matter the sport – external focus of attention is just more effective.

That said, progress in coaching technology, including sophisticated ways to measure performance, has added new layers to the debate on cueing.

Some aspects of coaching that have changed in the last two decades since the first study in 1998 are:

- Training – Wearable technology gives coaches key metrics on performance.

- Safety – Some wearable technology is geared toward protecting players, like smart helmets in the NFL and NHL.

- Video technology – Coaches can augment their instruction with video analysis techniques, which lead to more objective observation and measurable results.

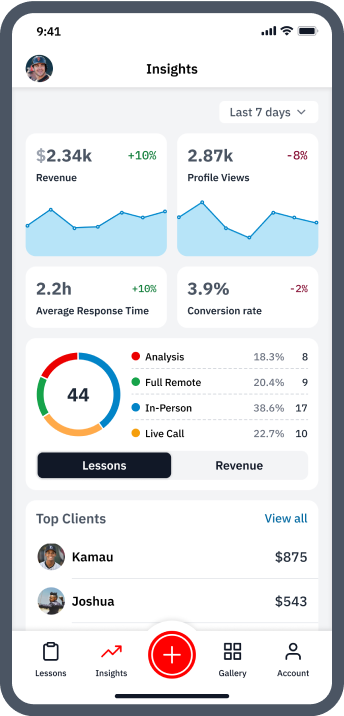

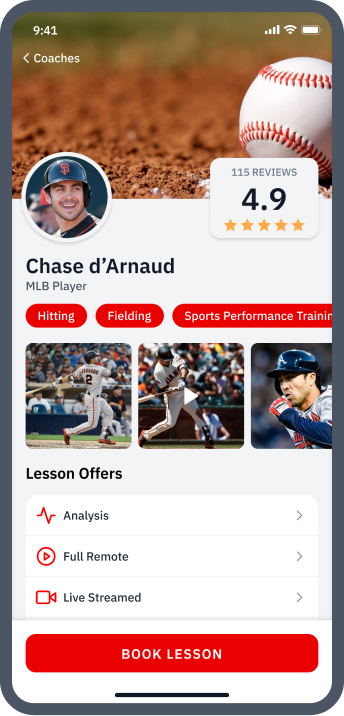

- Communication – Coaches no longer have to be in the same room with their athletes to give feedback. Remote coaching apps like SeamsUp can give coaches and players personal results, even from a world away.

With these modern advances, coaches today have a lot to factor into how they think about and structure their instruction.

Developments in internal and external focus studies have also incorporated these emergent technologies.

For instance, a 2010 study on increased jump height used electromyography (EMG) activity – a technique for evaluating and recording the electrical activity produced by skeletal muscles – to see if external focus cues affected neurophysiological mechanisms.

Hint for later in this guide: external cues did exactly that.

Wanna grow your baseball or softball coaching brand?

Get connected to new local and online lesson clients—along with all the tools you need to scale.

Download the free app

What’s the Difference Between Internal and External Focus for Baseball and Softball Coaches’ Cues?

We’ve discussed cueing and the body of research behind it, but haven’t dived deep into the actual difference between internal and external cues.

This next section will go into more detail on each type and explore the effectiveness of each one in different contexts.

Internal Cues

As a reminder, cues refer to what an athlete is thinking about when he or she is trying to perform an action.

And, again, internal focus means that athletes are thinking about something inside themselves or a part of their body.

Many coaches use these cues daily, like saying “load into your back hip when striding” to their hitters.

But a great deal of research has been done to evaluate the effects of looking inward during training or performance. And most studies show that internal focus isn’t as effective as external focus.

External Cues

External cues ask an athlete to think about something outside his or her own body. It’s usually something to do with their environment or a piece of equipment they’re using.

A cue like “show your back pocket to the pitcher” is focusing on external attention. These cues tend to emphasize the outcome rather than an internal action needed to perform the movement.

It’s widely believed that letting an athlete focus on outward stimuli reduces their conscious interference.

Basically, external-focused cues supposedly keep athletes from overthinking their performance.

Earlier, we cited the leading attentional focus researcher Gabriele Wulf, from the Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition Sciences at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, who has now spent the last 20 years studying internal and external focus.

According to Wulf, the more complex a task is, the more efficient external focus turns out to be.

She says that external attention is superior in two major domains:

- Movement effectiveness – This includes balance or accuracy in sports like baseball, softball, golf, soccer, tennis, and gymnastics, or motions like throwing, ball kicking, and juggling.

- Efficiency – Efficiency refers to force production, speed, and endurance. This benefits weightlifting, track-and-field, swimming, rowing, and kayaking.

Types of External Cues – The 3 D’s

There’s actually more than one type of external cue coaches can use.

They’ve been further divided into three categories:

1. Distance

External cues can reference the distance associated with an action the athlete needs to perform. Using objects to give instruction, like “sprint at the cone,” for example, will almost always contain distance elements.

Within this distance category, there are also close and far cues.

For example, a close cue might be “try to hit the inside of the baseball” because it has to be physically close to the batter to strike the ball.

A far cue example to a hitter might be “watch the pitcher’s hat with soft focus, and, as they get deeper into their delivery, try to hard focus on their release point.”

This is a far cue because the hitter’s attention is being directed at a point physically farther away from the batter’s box they’re standing in.

Some research into the subject has shown that beginner athletes do better with close-distance cues, whereas more experienced athletes do better with far-distance cues.

2. Direction

Directional cues use “towards” and “away” in their instruction. You may tell an athlete to jump toward something, or away from something else.

In hitting, this might mean telling a ballplayer to take their bat’s knob directly towards the ball.

Little research has been done to investigate the difference between towards and away, although it’s been suggested that “towards” cues might be more effective.

3. Description

External description cues are either action verbs like push, punch, and explode, or analogies that compare movements or aspects of movement to things like slingshots or rockets.

Not enough research has been done to prove these descriptive cues are effective, but anecdotal evidence and the opinion of many top-rate coaches say that they are.

Action verbs and analogies are descriptive, giving an athlete specific instructions to help them visualize what they must do or what they must try and embody.

Description cues should be experimented with by coaches and made to fit the interests and sensibilities of individual ballplayers whenever possible.

Telling a pitcher to “explode” off the mound might be more helpful than asking them to “push” off the mound, for instance.

Studies Specifically on Cueing in Baseball

Attentional focus has been conducted with athletes in a variety of sports, but a few have been done with baseball players specifically.

Ballplayers jumping

First there’s a 2017 study, for a master’s thesis, on the countermovement jump (CMJ) in collegiate baseball players.

The results showed a greater jump height for players who received external focus cues than those who received internal focus cues.

Interestingly, the paper also noted that participants showed a more accurate recall of internal-focused instructions, despite these cues being less effective performance-wise.

The author suggested that a greater degree of conscious processing, AKA, overthinking, may help explain internal cues’ weaker physical performance.

And we would add that the overthinking and internal rehearsal that it likely enabled is the reason participants were most likely to remember the internal cues more readily.

If you’re curious on how to use the tendency for internal rehearsal positively as a baseball or softball coach, check out our full guide on the Zeigranik effect.

Pitching instruction

The second study, also from 2017, was on elite youth baseball pitchers.

The authors of this recent study observed pitching instruction in the real world rather than setting up a test and devising their own internal and external cues.

Tellingly, they noticed that coaches’ cues were about 31 percent external-focused and a whopping 85 percent internal.

This shows that many coaches still favor this type of communication in baseball pitching instruction.

They also noticed that players said they preferred internal cues. Unfortunately, this study wasn’t set up to conclude that such internal cueing was more or less effective.

But their explanation for the prevailing use of internal-focused instruction – despite the mountain of evidence showing external cuing to be more effective – was a gap in sports science and sports practice.

Side Note:

This tendency to prefer things more just because we’re used to them has a name in academic and scientific literature – familiarity bias.

In fact, it’s so prevalent and common to nearly every situation humans find themselves in that psychologists actually refer to it as the familiarity heuristic – a heuristic is like a “rule of thumb” that mostly all people use when coming to any decision or belief.

And if you really want to geek-out on this familiarity heuristic, we’d add that its mechanisms run so deep that recent brain imaging studies concluded that we use completely separate areas of our brains when we encounter familiar versus unfamiliar situations.

The case for internal focus

Although a lot of evidence points to external cues being more effective, it’s clear that some coaches still prefer internal cues.

And prompting athletes’ internal focus might actually have benefits in certain contexts too.

Some physical therapists and other clinicians haven’t done away with internal-focused instruction entirely yet. They’ve cited studies that suggest internal cues are sometimes more beneficial to novice learners.

Proponents in this field would argue that part of why external cues work so well is because they allow the ballplayer’s athleticism and body awareness to take over without the slow and haphazard tendency to overthink things.

But completely novice learners may be responding favorably to internal cues because they have not yet built up the athleticism and bodily awareness to adapt to and fulfill the demands of a coach’s external cues.

When it comes to retraining an athlete after major injury, internal focus and faded feedback – as opposed to real-time feedback and external focus – tend to work better according to some studies.

We’ll explain what “faded feedback” is in just a bit.

But here it’s important to say that even though internal cues might work better for true beginners, more experienced athletes looking for effective in-game performances seem to benefit definitively more from external cues.

Internal focus might have its place in non-skill-specific-based physical training and recovery. They’re just not ideal for ballplayers who are pursuing serious performance goals within the game – even if they’re more used to hearing them.

Shifting Focus and Neurophysiological Changes

In another take on attentional focus, some researchers wanted to determine if there was a relationship between cueing and how an athlete’s nervous system takes in sensory information, AKA, neurophysiological effects.

These researchers used muscular activity via electromyography, or EMG, rather than movement accuracy or balance to assess movement effectiveness.

Why?

Because monitoring EMG activity leads to better insights when it comes to motor skills learning – helping researchers begin to understand why performance is enhanced so much under external focus.

In a study from 1994, researchers found that after a period of resistance training with a group of weightlifters, the athletes used less muscle area to lift the same amount of weight.

The conclusion was that neural adaptations in the muscles were responsible.

Basically, the muscles “learned” how to better lift the weight.

In 2001, Wulf and Prinz conducted a review of the existing evidence connecting attentional focus and neurophysiological changes.

And then, in the 2010 study cited much earlier in this guide, Wulf et al. built on all this evidence with more data by testing jump heights achieved with internal and external cues – whilst measuring the EMG activity of participants.

Their results reinforced what we already know about external focus – it leads to better results.

But they were also able to conclude that the reason it leads to better results is because muscle activity was reduced for groups using an external focus.

We now had evidence for the superiority of external cueing over internal, at the biomechanical level.

Explaining why external focus works this way, the authors of the jump height and EMG study said, “The predominant explanation for the attentional focus effects centers on the idea that an internal focus induces conscious control and constrains the motor system, whereas an external focus promotes automaticity in movement control.”

This “automaticity” means that not only are athletes’ movements more effective but they can also be learned more quickly.

How Coaching Cues in Baseball and Softball Affect Learning and Performance

By now, it should be clear that coaches’ verbal instructions have a significant impact on movement performance.

The jump height and EMG activity study cited in the previous section proves that cueing goes beyond performance outcomes too.

It affects the entire learning process – something much more difficult to measure in an athlete than outright performance indicators like slugging percentage.

The implications of attentional focus

The effects of external focus that we’ve discussed thus far are summed up wholly in what’s called the constrained action hypothesis (CAH).

The CAH states that,

Directing attention externally allows the motor control system to operate under non-conscious automatic processes by which movement occurs reflexively, leading to superior performance outcomes.

When focus is internal, it potentially activates the working memory, which can constrain the motor system and lead to less fluid movement.

To put it plainly, think about every time a coach has ever told you not to “overthink it” or to “get out of your head” when playing or practicing a sport.

Coaches and athletes have noticed for a long time that paying too much attention to what your body is doing can hinder athletic performance.

The CAH and the numerous studies that have tested it are simply scientific proof of this previously anecdotal insight.

It turns out that Yogi Berra was mostly right, as usual, when he asked, “How can you think and hit at the same time?”

As Yogi is implying, conscious internal thinking can hinder plate performance.

Long-term learning and faded feedback – the student becomes the master

Coaching cues are related to feedback.

Researchers note the difference between performance and learning – asserting that learning reflects a more permanent change.

If coaches and trainers rely exclusively on specific cues, they might see better performance in the moment, but impede progress in the overall learning process.

That’s because real-time feedback doesn’t always reinforce long-term learning.

Coaches and parents interested in long-term learning results, will do well to understand and apply concepts like the spacing effect and delayed learning, as well as microlearning.

But, as it stands, many a hitting or pitching instructor has lamented having to repeat the same concepts and cues week after week with their lesson clients.

Noticing this pattern of learning has led some expert researchers to try “faded feedback.”

In the context of baseball or softball, this concept may be particularly interesting, as one’s hitting or pitching coach is often not there to give external cues during live game at-bats.

This faded feedback strategy can be helped by setting up challenging and arousal-producing environments during in-person or remote lessons.

This can be accomplished by introducing stimulating drills, game-like scenarios with realistic stakes and clearly-defined performance goals, or replicating game-speed reaction times and movement looks in bp.

Increasing the intensity of the lesson environment can allow the ballplayer’s body to find personal solutions to specific pitches, locations, and situations that can become long-term learnings without the need for constant coach cueing.

Acute vs. chronic learning

Another way to describe short-term and long-term learning in motor skills is through the terms acute vs. chronic learning.

The goal for most coaches and athletes is chronic learning, and external cues have proven to boost such retention.

But they actually boost temporary learning as well.

By running and recording practice sessions with cueing then conducting retention tests on athletes, researchers have linked attentional focus to long-term motor skills acquisition.

Let’s dig into these insights.

Measuring results

Earlier, we went over measuring performance with EMG activity, but how else have experts assessed movement results related to attentional focus?

The two broad categories are Knowledge of Performance (abbreviated KP) and Knowledge of Results (KR).

Basically, KP is subjective and KR is objective.

Going one step further is something called intrinsic KR, which includes any internal markers athletes use to let themselves know they’ve performed the movement correctly.

An athlete’s own feelings and touchpoints from muscles, joints, or balance could all describe intrinsic KR.

This notion of highly-skilled athletes – because it’s only expert performers who use intrinsic KR – relying on internal biomarkers to perform at optimal levels would seem to go against all the research in favor of external cues.

However, in a blog post, physical therapist Randy Sullivan suggests that athletes aren’t even actually focusing inward when they move through a series of internal markers.

For example, when an elite hitter loads their rear hip at the start of a swing's separation, they might then feel their top-hand’s scapula fully engaged while their lead lead’s hip opens, which triggers them to fire their hands, etc.

The hitter’s attention isn’t on the specific internal action they’re performing, but on the next action in the coordinated series.

For Sullivan, this suggests more of an external focus than an internal one, putting the idea of intrinsic KR more in line with previous studies in attentional focus.

Final Thoughts on Cueing for Ballplayers and Coaches

The debate over external and internal cueing is extensive, with a fair amount of studies testing the topic and adding further nuances.

Verbal cueing is so important because it gets to the heart of sports coaching, which is the learning process.

Although the evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of external focus, there are some situational caveats.

In some contexts, like working with beginning or just recovering athletes, internal cueing might be more beneficial short-term.

As a coach, you don’t necessarily have to pick one type of focus over the other, but you should think about how you verbally instruct your athletes and consider how the way you teach impacts their ultimate performance and development.

Wanna grow your baseball or softball coaching brand?

Get connected to new local and online lesson clients—along with all the tools you need to scale.

Download the free app

About the Authors

Dr. Edgar Rodriguez DC, CCSP.

Founder of EROD Sports Medicine & Training

Doctor Edgar Rodriguez DC, CCSP, is recognized as a leader in both sports chiropractic and performance fields. He's currently an adjunct professor at the University of La Verne.

Mike Rogers

Co-Founder & CEO

Mike Rogers has spent a lifetime entrenched in baseball and softball as a player, a private instructor, a training facility owner, and the son of two college-level coaches.