The Ultimate Guide to Feel vs. Real in Baseball and Softball | Why Video Feedback is Essential For Players and Coaches

“Feel vs. real” is a concept that went viral within the baseball and softball communities a while back.

Part of the reason for this virality is that it finally gave a workable label to a phenomenon that many coaches and players had observed.

Feel versus real in baseball or softball refers to how our thoughts and feelings about what’s happening physically during such motions as swings or pitches aren’t always in sync with the actual movements we execute during in-game athletic performances.

This can be detrimental to current hitters and pitchers who might think they’re executing the right movements, but in reality, they’re not.

But it’s also worrisome for coaches looking to pass on their knowledge to the next generation of ballplayers based on what they feel brought them their success in the game.

In this guide focusing on hitting examples, you’ll learn about the feel vs. real effect and why video feedback is the answer to this problem.

We’ll cover the following:

- Defining feel vs. real

- Should the thought process match the swing?

- Feel vs. real and pro athletes

- The evidence-based reasons behind feel vs. real

- Video feedback and learning in baseball and softball

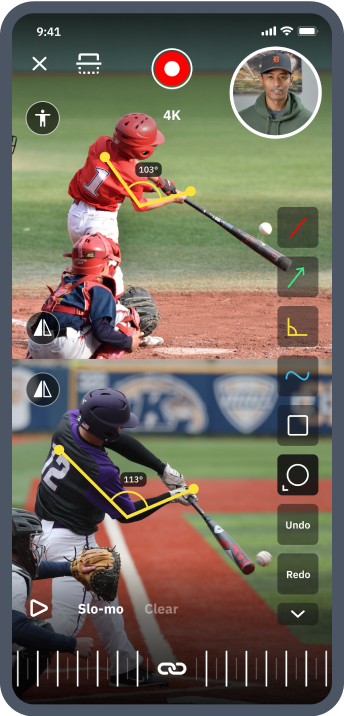

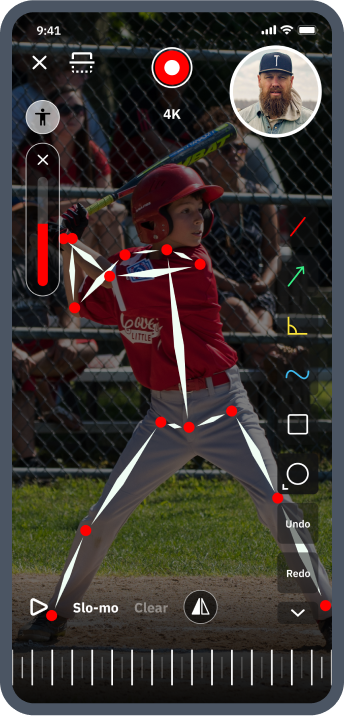

- Advanced video feedback tools for coaches and players

What Is Feel vs. Real in Baseball and Softball?

Again, feel vs. real is the phenomenon in baseball and softball – and most sports – when athletes’ in-game movements don’t match what they’re visualizing or feeling inside their heads.

As a hitter or pitcher, you might think you’re doing one thing with your swing or windup, but upon hearing feedback from a coach or watching yourself on film, realize you’re actually doing something completely different.

Take it from Ted Williams – feel and real are not the same

In an interview from 1986, three great left-handed hitters – Ted Williams, Don Mattingly, and Wade Boggs – got together to talk hitting.

At this time, Mattingly and Boggs were both at the height of their careers while Williams was helping out as a hitting coach with the Red Sox.

The article’s intro points out that these three hitters come from two very different philosophies on hitting.

Williams was a proponent of the hips, whereas Mattingly and Boggs focused on the head and shifting their weight.

As Mattingly starts talking about shifting his weight in his swing, Williams repeatedly tells him that what he’s saying doesn’t match up with his actual swing.

Williams pushes Mattingly to break down his swing and describe what he’s saying, at which point Mattingly finally responds,

I don’t know what my hands are doing and all that stuff. I just know what feels right.

The great Ted Williams knew that what you think you’re doing at the plate often isn’t in sync with what you’re actually doing.

He also knew that even baseball’s most successful hitters, like Don Mattingly and Wade Boggs, struggle to describe their true swing accurately.

Why does this matter for hitting coaches?

Professional baseball players don’t have to be good at describing their swing, as long as they’re performing well.

But as a hitting coach, you do have to know how to break down a good swing so you can explain it effectively to your athletes.

Understanding feel vs. real also makes coaches more aware of differences and nuances between listening to an athlete describe their thought process and watching that athlete’s actual swing.

P.s. Epic photos exist of the hitting talk between these three baseball greats. Check them out here.

More Pro Baseball Players Who Don’t Exactly Swing Like They Say They Do

Baseball bloggers and social media hitting pundits have cited numerous pro players as examples of the feel vs. real phenomenon.

The example you may already be familiar with is Alex Rodriguez.

The legend became central to all things feel vs. real when he published a sort of anti-launch-angle video entitled “HOW TO HIT HOME RUNS | TIPS FOR THE BEST APPROACH AT THE PLATE.”

In the video, Rodriguez demonstrates and offers the advice echoed by so many other elite hitters both before and after his time: swing down and through the ball.

This is certainly what one of the top power hitters of all time thought and felt about his swing.

But analyzing tape of just about any of his 696 career home runs reveals that this cue and feeling translated into something quite different in execution.

Similarly, Baseball Rebellion analyzed Mike Trout’s swing and compared it to a promotional training video he made.

In the training video, Trout also talks about swinging down on the ball. When slowing down and picking apart his demonstration swing, many have pointed out how the potential zone to make contact with the ball shrinks as the barrel approaches contact.

When you compare this training demonstration to footage of Trout’s swing during a live game, you see that he’s not really swinging down on the ball at all.

Oftentimes, watching some pro’s in-game swing might benefit up-and-coming hitters more than listening to them talk about their swing.

Should the Thought Process Match the Swing for Hitters?

As we’ve established, a hitter’s thought process doesn’t always match their swing.

But as a hitting instructor, it’s sometimes important to gauge your hitters’ mental processes as they work through their swing – even though they usually won’t be able to describe the reality of what they’re doing accurately.

Why?

As we’ll explore below, it still gives you helpful insights into their execution.

Maybe a young hitter is kicking their lead foot up in a way that doesn’t load their back hip and leaves them out of balance and un-separated when it plants back down.

And they’ve added this big lead kick because they’re trying to emulate a particular pro’s swing and not exactly doing it correctly.

This is a pretty common scenario.

But as a hitting instructor, you won’t know the why behind this player-made adjustment unless you ask your hitter about their thought process.

And why’s matter.

Knowing what a hitter is trying to do and why can make fixing the issue much quicker and more comprehensive.

You could simply show the player video footage of themselves compared to the person they’re purporting to mimic, for example.

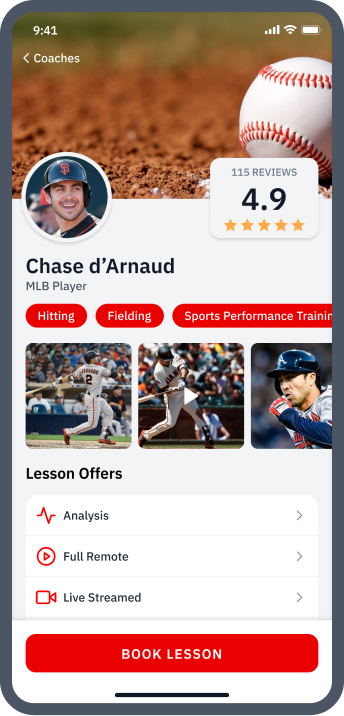

Wanna grow your baseball or softball coaching brand?

Get connected to new local and online lesson clients—along with all the tools you need to scale.

Download the free app

As the feel vs. real phenomenon shows with major league hitters, the thought process does not have to match the actual swing to lead to successful outcomes.

As long as a hitter executes an aggressive and athletic swing with a good bat path and is consistently able to square up the ball, what they’re thinking about when crushing it feels much less important. Right?

But, when working with hitters who are struggling, it’s still worth finding out what’s going on in their heads and trying to uncover how those thoughts might also be contributing to poor execution.

Regardless of how much knowledge you have or how compelling you are as a coach, each hitter will interpret your instructions in their own way – so it’s always best to help them achieve their perfect swing and not the perfect swing.

Does Filming Baseball and Softball Hitters Help? | The Secret Power of Swing Analysis

Helping hitters fine-tune their real mechanics and even relay thought processes is much easier when using video analysis.

Video can pick up the slightest deviations in the swing, which would be imperceptible to the naked eye. It also gives hitting coaches a more tangible and objective resource to fall back on and compare with when guiding athletes.

A great way to help batters learn is by having them watch a recording of themselves swinging.

Your player can see what you see, and you can point out what’s going wrong and what’s going right.

These benefits of reviewing swing footage are pretty obvious to seasoned instructors and team coaches, but there’s another often-overlooked and not talked about aspect to this practice that may be the real secret to its power:

The simultaneously shared view of going over tape together removes many unhelpful emotions from the instructional process.

Giving advice to a hitter who’s all warmed up and actively struggling during BP or right after unsuccessful in-game at-bats is less than ideal.

Frustration and other feelings will be highest at these times.

And when emotions are running high, it’s hard enough not to get defensive when being told feedback, let alone actually internalizing and actively implementing that feedback.

It’s also just easier to psychologically reject or discount hearing what feels like one person’s – the hitting coach’s – opinion.

And it allows the player to step back and take a more cool-headed scientific approach to analyze and address what’s not working.

How Baseball and Softball Players and Coaches Should Think About Using Pro Player Footage as Examples

When watching footage of a professional ballplayer at bat during a game, there’s a lot more going on besides the swing mechanics.

There’s timing, type of pitch, and pitch count. These factors will also affect the swing, and they can be hard to train for – let alone even perceive from your living room.

Also, many of the pro example videos that players and coaches watch and share online are of home runs.

But not every successful swing leads to that outcome. And only analyzing home runs risks at least slightly skewing your sample data and the logical conclusions you might make on mechanics.

That said, this next section of our guide is better served by zooming out a bit and going for a much more nuanced and complicated point.

🤞 Here goes nothing.

The Journey from Mimic to Master

We want to explore the sometimes messy process that young hitters face when experimenting with the advice and mechanics they see from their favorite MLB players on the road to eventually discovering movement patterns, cues, and approaches that work best for their unique physical and mental attributes.

Craftsmen, artists, and athletes all go through this same process of making something established as their own.

In fact, any child development researcher – or parent for that matter – can tell you about the fundamental role mimicry plays in how human beings learn and grow.

And whether talking about famous artists or cranky toddlers, the transition from mimicking the example behaviors, styles, and insights of others into finding and expressing uniquely individual thoughts and actions is always a life or career-defining one.

Young ballplayers can and should still take advice and learnings from professional athletes and experiment with incorporating them into their still-developing hitting style.

The experimentation and inspiration that engaging with expert examples provides young hitters are vital.

Who knows how many ballplayers’ athleticism and more efficient bat paths were first unlocked while attempting a Ken Griffey Jr. impression during a Wiffle ball game.

Not to mention the extra tee work and dry swings it inspired for those of us who dreamed of having a swing half as sweet.

But, ultimately, up-and-coming hitters will only feel truly comfortable at the plate with their swing, not someone else’s.

Another thing for both players and coaches to keep in mind in this regard is the body’s limitations.

You might watch Mike Trout’s or Josh Donaldson’s swing and want to copy and paste it exactly.

But this would be impossible.

Your hitter could have a completely different body type than Mike Trout – maybe his shoulders are set further apart, his arms are longer, and his legs are shorter. And maybe he has specific mobility gifts or constraints from top to bottom that all contribute to his movements.

Basically, Mike Trout has the perfect swing for Mike Trout.

He’s trained consistently to optimize his swing to his body type along with his other unique physical and mental attributes – making the most of his own advantages and limitations.

It’s also possible that Mike Trout’s training regimen and discipline as a top-level, professional athlete is beyond what most youth, high school, or even college athletes have access to or the ability to execute.

So hitters shouldn’t strive to copy a pro’s swing exactly – at least not forever.

A quick and related aside:

Though Picasso is known for his wildly unique and original Cubist and Surrealist works, he had formal artistic training from the age of seven with his father – an art professor and instructor – who believed that the disciplined and systematic copying of long-gone master artists’ works was the only path to greatness.

And after outgrowing his father’s tuteluge in his early teens, he attended three of the top art schools in Spain and eventually traveled to Paris to be at the epicenter of more cutting-edge expression before developing his own revolutionary style.

The point of this brief art history lesson is that employing personal coaches and mentors – and actively engaging with expert examples – together form a mix of influences that are essential to learning and mastering any worthwhile skill.

The Science Behind Feel vs. Real in Baseball or Softball – Plausible Explanations for the Phenomenon

Why does the feel vs. real occur?

It’s a challenge to explain why our thoughts can’t directly translate into bodily movement or why we have trouble verbally or physically articulating these movements to others after the fact.

Below are two potential explanations, though.

1. Neuroplasticity

You might be asking, “Neuro-What?”

It refers to the physiological changes in the brain that happen due to interactions with our environment.

The connections among the cells in our brains constantly reorganize in response to our changing needs.

And those of you who are private instructors or teams coaches, are literally causing structural and organizational changes to the brains of the ballplayers you work with.

Here’s the very simplified explanation of exactly what’s happening during lessons:

- The brains of your newest ballplayers actually expand in volume due to your teaching interactions.

- Then, once you’ve worked with that client for a while, the parts of their brain that you have helped expand begin to stabilize back to their pre-lesson size, and, in turn, their body’s more consistent movement patterns start to emerge.

This directly coincides with connections in the player’s brain organizing together more and more efficiently to execute these learned movement patterns with periodically less and less brain and bodily effort. We are optimizing machines, after all. - Next comes internalization, when both you and the ballplayer’s own brain are working together to further get rid of unnecessary and unhelpful movements.

Researchers call this step “pruning” and it allows the player to fully internalize the mechanics and understandings that you introduced. - This so-called pruning eventually gives way to the process of developing a bit of personal style to their swing or pitch.

This uniqueness is partly necessitated by what’s happening in the brain but also by the athlete’s own unique body lengths, mobility, and strength.

This is when the ballplayer begins to own the process that you’ve helped facilitate.

Neuroplasticity and feel vs. real

Okay, so what does neuroplasticity have to do with the feel vs. real idea?

Remember in the explanation above that neuroplastic learnings and subsequent re-organizations – like all of our brains and body’s processes – always seek the most efficient and energy-saving routes to accomplish goals.

Well-trained ballplayer’s brain cells have reorganized enough through practice to need very little conscious effort to execute the correct response in terms of posture, bat path, etc.

This is good because hitters don’t have time to think consciously about what each link in the chain is or should be doing in the roughly 0.40 seconds after a pitcher’s release.

That time is instead spent determining if it’s a strike or a ball and reacting to the pitch’s type, location, and speed.

This also may partially explain why elite professional hitters struggle so much to explain their own form.

They’ve long-committed the movements to muscle memory, so that consciously accessing exactly what they are doing at any given link in the kinetic chain is nearly impossible.

To do so would involve unraveling all the efficiency that they’ve cultivated over a lifetime just to make it a clunky conscious process all over again.

And since conscious memory is mostly out of the picture, ballplayers are only left with impressions of how they felt leading up to and directly after the swing.

The iconic Maya Angelou once said:

I’ve learned that people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

Elite ballplayers, whose brains have fully internalized everything that goes into a successful swing outcome, may not know or remember what’s happening at every juncture of the movement chain’s energy transfer, but they know how it makes them feel.

The more emotional thoughts and signals stay long after the brickdust that exploded off a hammered baseball has settled back to the ground; stays as the slugger rounds the bases and takes in the helmet taps and hugs of home plate; and stays when talking about what went right with a teammate an inning later in the dugout.

Of course, many modern professional hitters can and do use video analysis and feedback, often with the help of expert hitting consultants and the latest tech, to explore their kinetic chains in more detailed and systematic ways than previous generations.

But sessions with real kinematic sequencing models and the like, have a long way to undo all the “feels” gained from a lifetime of practicing the art of hitting.

This explanation for feel vs. real is the most compelling to us, but it’s not the only one out there.

2. Proprioception

Another possible explanation for feel vs. real is proprioception.

Your body has neurons called proprioceptors located in your muscles, tendons, and joints.

These neurons send codes to your central nervous system, which, along with your other sensory systems, gives you an idea of your body position, movement, and acceleration.

They’re sorta like the accelerometers and gyroscopes that power a bat sensor, like Blast Motions’, insights.

Okay, but how can proprioception explain the feel vs. real phenomenon?

Your proprioceptors are just one of three sensory systems your body uses when it comes to balance and movement. Your body also relies on both your vision and your vestibular system AKA, your inner ear.

Sometimes, your proprioceptors can be inaccurate, sending your brain the wrong feedback.

In such a case, you might think your body is doing one thing when it’s actually doing another.

Inaccurate proprioceptors could be one explanation for feel vs. real.

If an athlete’s sense of movement is off, they won’t always know it.

So when they try to explain it to someone else, it doesn’t match up with reality.

In terms of movement, your vision is more reliable than your proprioceptors. Your eyes can perceive more than your neurons can feel.

Sport scientists and physical therapists know this, which is why they emphasize video feedback in training and rehabilitation so much.

It’s also the reason clinicians will use mirrors with their patients and half the reason why gyms have mirrors on the walls – the other half is playing to vanity, of course.

Why Video Feedback is Essential for Baseball and Softball Players and Coaches To Solve Feel vs. Real

If what you’re feeling your body do isn’t aligned with the results you want to produce, then the solution seems simple.

Record yourself, or have a coach record for you.

The feel vs. real phenomenon is just one of many reasons why video feedback is beneficial to sports training.

Video provides an objective record of an athlete’s performance.

A coach can review their hitters’ mechanics by watching and re-watching the video, looking for things he or she might have missed during a live session.

Setting up cameras at different angles makes video feedback even more useful – one camera can’t capture every muscle that’s working in a hitter’s swing.

The most common angles to film a hitter are from the side (face-on) and from the rear (but slightly on the hitter’s open side).

And with a motion that’s as complex as a baseball or softball swing, advanced video technology like high-speed cameras is almost a requirement to get a good analysis.

Luckily, the phones in all of our pockets more accurately capture motion and have better resolution than the bulkiest and most expensive camera of previous eras.

Video feedback has evolved significantly since it was first used in professional communication settings. It has practical applications today in business, education, and sports.

Video feedback provides a powerful solution for athletes who want to get ahead – or just beat the feel vs. real dilemma.

Video Feedback and Learning Outcomes

Video feedback was first used officially as an education tool at Stanford University in 1963.

Around the same time, a new model of teaching was developing, called microteaching.

Video feedback worked well with this new bite-sized approach to instruction.

Lessons could be chunked into small sessions during which students performed their target behavior then reviewed themselves on film with instructor feedback.

Video feedback works because it allows people to see themselves objectively “from a distance.”

Once instructors saw the positive results, the use of video feedback to train communication professionals soared. It helps build specific skills, like how to deliver a sales pitch or how to conduct a hiring interview.

And it didn’t take long for researchers to apply this successful methodology to the acquisition of motor skills in sports.

Video feedback in sports

Studies on behavior modification in sports started as early as the 1970s.

One of the first was a 1974 study by Thomas L. McKenzie and Brent S. Rushall, which assessed whether competitive swimmers self-recording their attendance at training sessions would improve the team’s overall attendance rate.

The swimmers would check off the completion of a unit of work during practice, which made the training environment more productive.

While it didn’t use video feedback, this study was one of the first to show that self-reflective behavioral procedures can have a positive impact on athletes’ performances.

Subsequent studies on athletes’ behavior in the training environment showed similar results.

Eventually video feedback was introduced as a tool not just for modifying behavior in training, but for outright performance improvement in a 1980 study on tennis serves.

Roberta Rikli and Gregg Smith evaluated tennis serves of four groups, three of which received video feedback during different phases of instruction – beginning, middle, and end – and one which received no video feedback.

The results showed that video feedback had positive effects on performance, as the three groups who received it improved over the one group that didn’t.

This study paved the way for expanded use of video feedback in athletic training. As well as further evidence for its efficacy.

And you don’t need to take out word for it – at the very bottom of this guide we've included a small sampling of related research that we pulled from our ultimate guide on why video analysis is essential for baseball and softball.

Today, video feedback has become an almost indispensable tool for elite athletes and their coaches across sporting endeavors.

Video modeling

Video feedback has developed several variations in the over fifty years since its first use.

One type of video feedback analysis that’s especially pertinent to the feel vs. real debate is called video modeling.

The process of video modeling usually goes as follows:

- Film an athlete as he or she performs a movement – you should target the movement you want to improve beforehand

- Show the athlete a recording of an expert or professional-level athlete completing the same target movement

- Compare the expert’s recording with the athlete’s own recording, discussing differences and how the athlete can improve

In a study on youth gymnasts and video modeling, Eva Boyer et al. showed that video modeling significantly improved the athletes’ performance.

Specifically, they found that video modeling coupled with instructor feedback resulted in the most improvement.

Video modeling can indeed be a great tool for athletes, but coaches should shy away from just having the athlete watch the expert and saying, “Do what they do.”

As we’ve covered at length above, trying to copy an expert’s movements exactly with neither context nor professional guidance is not a great long term idea.

For this reason, video modeling should be accompanied by commentary and instruction from a coach or trainer.

An athlete needs to make sense of what they’re seeing in an expert example and compare their current mechanical status objectively.

Otherwise, they could interpret and perform the move incorrectly – creating a potentially detrimental feel vs. real relationship.

How to Get the Most Out of Baseball and Softball Video Feedback with SeamsUp

By now, you know that to combat the feel vs. real phenomenon elite hitters and pitchers should employ video feedback.

We built the SeamsUp app from day one to harness the power of video feedback, along with other modern approaches to accelerated skill acquisition.

Broadly, there are two different approaches to learning:

Synchronous learnings happen in real-time. And asynchronous learnings don’t.

SeamsUp gives parents and their ballplayers the ability to try out both styles of learning – as our elite coaches can offer just about every kind of in-person or remote lesson type imaginable.

Final Thoughts on Feel vs. Real and Video Feedback Analysis

While feel vs. real is a ubiquitous phenomenon, coaches and trainers aren’t positive why it happens.

We are curious to hear what you think of the two hypotheses that we proposed above.

But, what is known is that coaches should be able to see the unique potential in each of their athletes and employ the right techniques for helping them optimize their movements.

And to get the most thorough, objective analysis of hitting or pitching performance, coaches and players need video feedback.

Watching themselves perform, coupled with professional guidance, teaches players about their own movements and can help them overcome the feel vs. real issue – or, at the very least, ensure that it doesn’t get in the way of their success.

Unlock your ballplayer’s full potential

Find the perfect vetted coach to build a solid foundation or take your player's skills to new heights.

Download the free app

About the Authors

Dr. Edgar Rodriguez DC, CCSP.

Founder of EROD Sports Medicine & Training

Doctor Edgar Rodriguez DC, CCSP, is recognized as a leader in both sports chiropractic and performance fields. He's currently an adjunct professor at the University of La Verne.

Mike Rogers

Co-Founder & CEO

Mike Rogers has spent a lifetime entrenched in baseball and softball as a player, a private instructor, a training facility owner, and the son of two college-level coaches.